Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

Combining a love for motorsport racing and metal fabrication

A Utah-based metalworker's fascination for CNC tube bending opened the door for two businesses

- By Lincoln Brunner

- July 29, 2022

- Article

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

When Rob Parsons suffered a paralyzing back injury, rather than call it a setback, the Salt Lake City metalworker turned it into an opportunity to pursue two fascinations: racing and metal fabrication. That, in turn, led him to starting up two different business: Bending Solutions and CageKits. Above, Parsons works out the particulars of a customer’s car chassis. Images: Rob Parsons

If you had a broken back and just lost the use of your legs, you might be expected to, you know ... stop doing the thing that put you there. Not Rob Parsons. In fact, lying in his hospital bed 11 years ago, recovering from a motorcycle racing wreck, Parsons had one prevailing thought: How do I get back on the track?

Motorcycles were clearly out, but the fever that Parsons had fed ever since high school, racing cars with his dad, still burned.

“Once I got back home, I really wanted to get back into racing cars again, and I took it upon myself to figure out a way to do that,” said Parsons, now 36.

After six months of rehab and figuring out how to use his new wheelchair, Parsons dove into developing a hand-control system for his racecar that worked far better than what he’d found on the market. The kit he created combined a pneumatic clutch, a closed-loop shifting system on a standard H-pattern gearbox, an accelerator, and a hand brake, all operated by his left hand. That freed his right hand to steer—perfect for the drifting style of racing he loved.

“It’s something that had to be done again,” Parsons said about racing. “It proposed a problem that I needed to solve—to figure out how to do it again. No one made hand controls that were adequate. Or they were over-the-top expensive but still didn’t do what they needed to do. So, I decided to make my own and go racing. Believe it or not, it worked pretty good the first try.”

So good, in fact, that it both got him doing what turned his crank and set him on a career path that led to running two fabrication businesses. Even before the injury, Parsons’ love of cars birthed a fascination with metal fabrication. Postrecovery, that fascination led him to work in several job shops, where he learned welding and how to operate press brakes, tube benders, and plasma tube cutters. Along the way, he actually lived across the street from a shop run by future business partner Brad Kalmar, who welcomed Parsons into the shop and let him hang around whenever he wanted. So Parsons, ever the knowledge sponge, learned how to use Kalmar’s laser cutter just with practice and observation.

One technology that caught Parsons’ imagination early on was CNC tube bending. For Parsons, the more technologies he learned, the more he wanted to accomplish, an urge that eventually pushed him to create not one but two businesses in Salt Lake City—Bending Solutions, a fabrication job shop that he owns 50-50 with Kalmar, and CageKits, a designer and manufacturer of custom roll cages mainly for off-road and racing vehicles. Parsons’ quantum leap came with 3D scanning.

“When I got my hands on the [3D scanning] stuff, I just went crazy with it,” said Parsons, who meticulously scans vehicle chassis interiors to create ultratight custom roll cages. “I’ve seen a couple of companies overseas that were doing it on a pretty big scale with roll cage kits. And they’re pretty successful. But America had a huge hole in the market for this kind of product. So I thought, ‘There’s something here.’ And that’s where I dove into it head first with 3D scanning.”

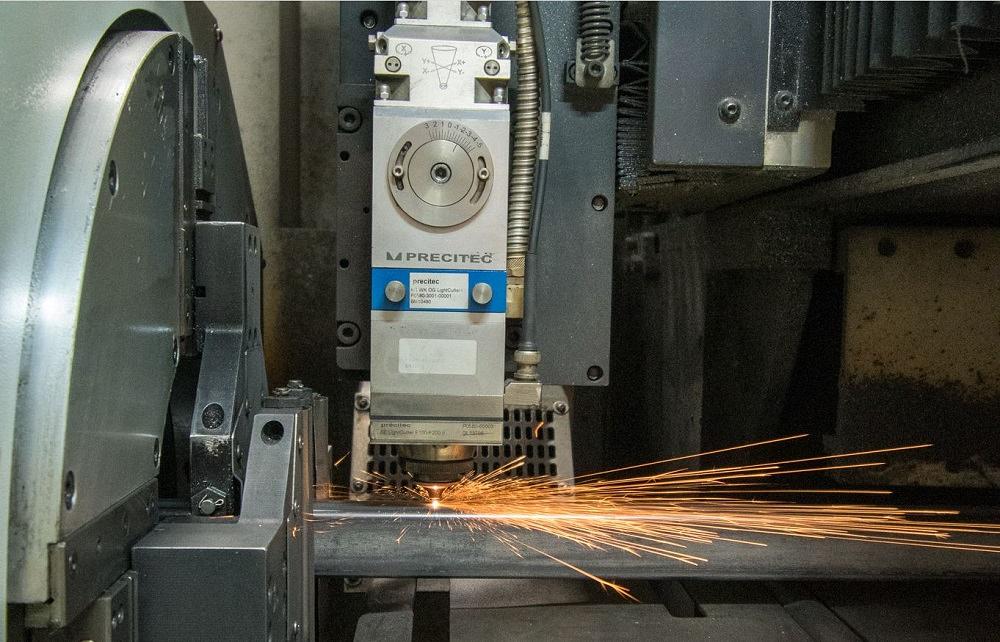

To bend and cut the tubes that comprise the cages, Parsons and his colleagues started with an NC tube bender and a plasma tube cutter—economical systems that allowed them to create a rapidly growing business. But when Parsons decided to venture into new technological territory with a tube laser, he ran into what might be called a language barrier. More to the point, he couldn’t find software that would accurately plot tube intersection locations and transfer that data to his new equipment.

“I had to get very creative with how I was going to get that information to the laser cutter,” he recalled. “That’s a little bit of a trick because we are one of the only companies, if not the only company, that does this for roll cage kits. And I had to write some software and get creative with it—how to make that information usable for the tube laser cutter.”

Parsons defied what conventional thought said his personal limits should be, having a machine manufacturer tell him that what he wanted to do with tube cutting couldn’t be done simply fueled his desire to do it. All it took was a working knowledge of the plasma cutter and laser cutter G-code and a vision for what he wanted in the end.

And just like Parsons defied what conventional thought said his personal limits should be, having a machine manufacturer tell him that what he wanted to do with tube cutting couldn’t be done simply fueled his desire to do it. All it took was a working knowledge of the plasma cutter and laser cutter G-code and a vision for what he wanted in the end.

“It’s a piece of equipment and it just runs off of software,” an indignant Parsons said. “If you’re creative enough or have the drive to figure it out, you can do what you want. So that’s where I started out—making essentially my own postprocessor for the machine to interpolate the files that I had available to me.

“In the grand scheme, it’s using all the information from [the machine company] and stripping it of all the stuff we don’t need. I create a new G-code file based off the geometry that I have available and then put in all the … M-codes for the functions for doing what I need it to do.”

Once again, necessity proved to be the mother of invention—or in Parsons’ case, a technology investment.

Along with that switch to a tube laser, Parsons and Kalmar decided to step up from just using an NC tube bender to investing in a Star Technology Starbend 800 CNC rotary draw tube bending machine. With that purchase from Innovative Tube Equipment Corp. (ITEC), Parsons and Kalmar launched Bending Solutions in Salt Lake City. Coupled with ITEC’s TubeWorks software, the new technology gave Parsons a tool that far exceeds his former capabilities.

“It started to get painful enough with respect to bending that our orders were harder to get out in a timely manner,” Parsons recalled. “We wanted to increase quality, and I always wanted to get into a CNC tube bender. That’s when Brad and I started Bending Solutions.”

For the most part, CageKits creates its products from the same kind of steel DOM tubing—mostly 1.5 or 1.75 in. OD—used to create many car and chassis parts, though a few applications call for chrome-moly or other more exotic alloys. Wall thicknesses most often range from 0.083 to 0.120 in. However, the shop often runs tube as large as 3 in. OD with 0.250-in. walls.

Parsons said he is still running all his parts through his old bending machine first to get his flat patterns with scribes and tube locations set before finishing them on the Starbend. Using his special cocktail of machinery and software, Parsons and his crew can reproduce virtually anything to match the profiles his 3D scans call for.

“Once the machine showed up, we just hammered down on it, learning how to use it and then changing all our CAD files over for CageKits to work with the machine,” Parsons said. “And then we just use TubeWorks for programming or we’ll program it by hand. It just kind of depends on what we’re doing.”

Day to day, Parsons is scanning and bending and cutting his way to solutions for his customers. But what he’s really doing is using technology to reinvent the creation process—namely, one that gets a concept from computer to car frame directly with little or no scrap. And with the current environment for steel prices and availability, that capability has never been more timely.

Bending whatever shape tube is necessary for the job helps Bending Solutions make the most of its investment in a Startechnology tube bender.

“With Rob, it’s shortening that software interface between first part and right part, even if something is complex—those challenging parts,” said Brian Julien, owner and founder of ITEC, who sold Parsons the Starbend 800 and helped him get it up and running. “People don’t want to be throwing away any more scrap than they have to, especially right now. You’re talking about getting to that right part the quickest way possible.”

For Parsons, it’s about providing a product that takes guesswork and intermediary fitment out of the equation.

“One of the unique things with this digital design mentality is that we don’t do prototypes anymore,” Parsons said. “It’s new design and direct to sale. With the 3D scan, there’s no questioning where things sit. Our roll cages are the tightest-fitting roll cages, period. They touch on the sheet metal [of a chassis] in all aspects. You can install it in eight hours, whereas a roll cage usually would be one week, 60 hours of work to put something in by hand.”

With his unique combination of creativity, software savvy, gear-headedness, and risk-be-damned ambition, Parsons is continuing to rocket forward on the road he began traveling the first day he jumped back to the racetrack from his recovery room. And he has no intention of looking back.

“It took a little bit of getting used to, to get back into it,” he recalled. “But you know, the first outing with the car was incredible. And it was a very empowering feeling too.”

About the Author

Lincoln Brunner

2135 Point Blvd.

Elgin, IL 60123

(815)-227-8243

Lincoln Brunner is editor of The Tube & Pipe Journal. This is his second stint at TPJ, where he served as an editor for two years before helping launch thefabricator.com as FMA's first web content manager. After that very rewarding experience, he worked for 17 years as an international journalist and communications director in the nonprofit sector. He is a published author and has written extensively about all facets of the metal fabrication industry.

About the Publication

subscribe now

The Tube and Pipe Journal became the first magazine dedicated to serving the metal tube and pipe industry in 1990. Today, it remains the only North American publication devoted to this industry, and it has become the most trusted source of information for tube and pipe professionals.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Trending Articles

Team Industries names director of advanced technology and manufacturing

3D laser tube cutting system available in 3, 4, or 5 kW

Corrosion-inhibiting coating can be peeled off after use

Zekelman Industries to invest $120 million in Arkansas expansion

Brushless copper tubing cutter adjusts to ODs up to 2-1/8 in.

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI